Making Health Care Affordable

- Introduction

- Billie Farnum and the Great Society

- - Mental health care

- - Eldercare and the impetus for Medicare

- - The Medicare debate

- - Medicare and Michigan seniors

- Mike Rogers and health care reform in the Bush Presidency

- - Reforming Medicare

- - Prescription drug coverage

- - Healthcare Savings Accounts

- - Private solutions

- - Patient bill of rights

- Conclusion

- Sources

50 Years of Health Care and the U.S. Congress

An online exhibit showcasing items from the Michael J. Rogers Congressional Collection and the Billie S. Farnum Papers.

Congressional Representatives from both political parties have tried to fix health care costs in the United States for generations.

Healthcare rhetoric in today’s political climate is divisive. Americans identifying as conservative often argue against the government having a role in health care. Americans identifying as liberals, meanwhile, often argue for further expansion of the government's involvement. Yet, this disparity is an aberration.

Reforming the manner in which Americans pay for healthcare has long been a bipartisan pursuit. Efforts by the federal government to bring health costs down have been taking place for sixty years. The Democratic and Republican parties have each attempted to reduce the costs of healthcare.

The exact manner in which each party chose to cut costs has, however, differed in fascinating ways.

This exhibit is about two Congressional representatives who tried to cut down healthcare costs.

These representatives were from different parties and lived in different contexts. Yet both wanted to use government intervention to cut health care costs.

Billie S. Farnum

(D-MI, 1965-1967)

Michael J. Rogers

(R-MI, 2001-2015)

The first attempt to use the government to bring down healthcare costs was under Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1956.

Eisenhower provided healthcare to the dependents of military personnel. In addition, he pushed to provide federal subsidies that helped states provide healthcare for the poor. A third program was the Forand Bill of 1957. This bill called for 60 days of hospital care, as well as surgical and nursing home benefits for all Social Security beneficiaries.

The American Medical Association opposed all three programs and hired a public relations firm to fight the passage of these bills through Congress. They called the Forand Bill “socialized medicine,” which tapped into Cold War fears of Soviet incursions into the United States.

These attempts to halt government intervention into healthcare were successful for years.

----

Text and exhibit materials by David Wagner (August 2017). Updates and website design by Dominique Daniel (February 2018).

All documents and materials are from the Michael J. Rogers Congressional Collection and the Billie S. Farnum Papers. Courtesy of Oakland University Libraries' Archives and Special Collections.

Billie Farnum and the Great Society

Representative Billie S. Farnum (1916-1979) was a congressman from Michigan’s 19th US district.

Farnum was a Saginaw native. He was an important official in the United Auto Workers and Congress of Industrial Organizations unions in the 1950s and early 60s. Farnum went on to serve as a key aide to Michigan Democratic politicians and the Michigan Democratic Party by the early 1960s, and was elected to Congress in 1964.

Healthcare was a prominent focus of Farnum’s agenda upon his election.

He was a dedicated advocate for research and funding for several neglected aspects of American health.

Two areas Farnum concentrated on were funding for mental health and child retardation treatment.

The government since the late 1950s had focused upon research for further medical advances, rather than helping patients directly. This was due to the outcry against attempted government intervention into health care in the late 1950s. There was not a great deal of momentum behind providing direct assistance to patients already in need. The landscape changed with Democrat Lyndon Johnson's victory in 1964. There was now a mandate to put more comprehensive reforms on the table.

Mental Health Care: A Neglected Issue

For much of the early 1960s, the federal government limited its role in healthcare to providing piecemeal improvements. President John F. Kennedy, for instance, had provided federal funds for the construction of new local mental health centers. These centers aimed to keep mental health patients out of over-crowded and costly mental hospitals.

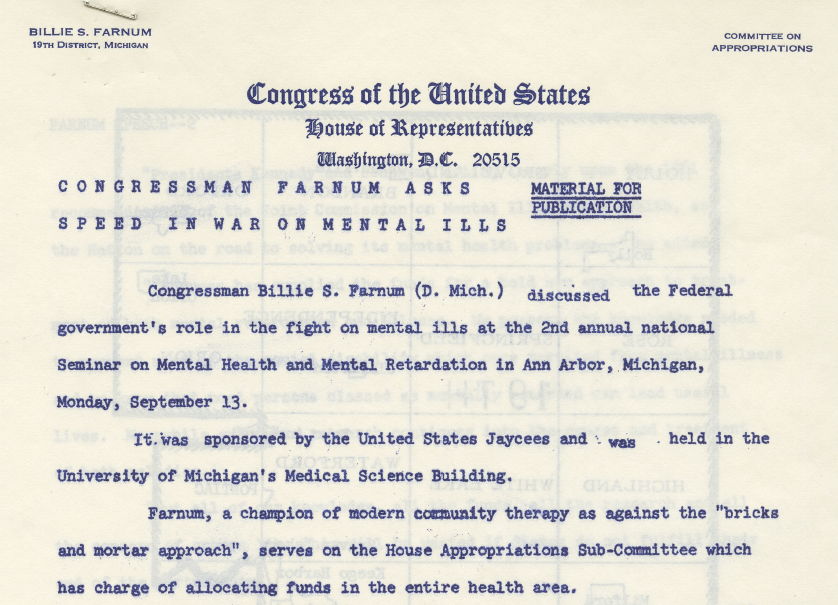

This press release shows that Farnum supported expanding this idea.

He claimed mental health centers allowed treatment to be completed in six months instead of 11 years.

Press Release: Congressman Farnum Asks Speed in War on Mental Ills

(Box 4, Billie Farnum Papers, Oakland University Libraries' Special Collections)

Before Medicare, Farnum framed federal assistance as improvements to efficiency and cost-cutting measures. This was because there was substantial cultural resistance to federal intervention in healthcare.

Arguments in this document are a good example of this.

Here, Farnum does not make moral arguments. He argues that community centers were cost-effective for taxpayers. He claims that the centers enable patients to return to their occupations and contribute to the economy faster. This, he said, would cut welfare costs nationwide.

Farnum sought to frame the use of federal dollars for community centers as cooperation between the federal and state governments: not unilateral federal intervention. He argued this cooperation would make healthcare more efficient.

Eldercare and the Impetus for Medicare

Before Medicare, the federal government did not provide healthcare assistance on a large scale. Only military veterans or their dependents had government health insurance. Retired Americans had to purchase their own health insurance plan if they wanted preventative care.

This was an intensely costly proposition, because insurers considered the elderly to be bad insurance risks. Only half of older Americans had any health insurance coverage at all. 47 percent of elderly families had incomes below the poverty line. Many elderly Americans relied on emergency room visits. Such visits were often prohibitively expensive, and could result in bankruptcy.

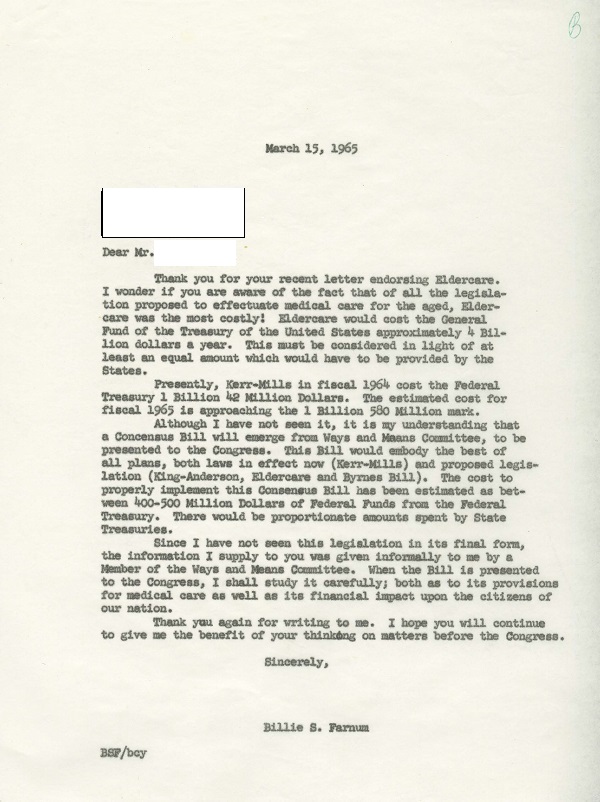

“Letter to constituent,” March 15, 1965

(Box 6, Billie Farnum Papers, Oakland University Libraries' Special Collections)

This document shows Farnum explaining the immense cost of health care for elderly Americans. As Farnum explains, the costs of so-called “eldercare” were staggering.

By 1965, the public was ready for government intervention in health insurance. Statistics showed that the public now rejected the AMA's arguments. That year, President Johnson and Congress created Medicare.

Medicare was federal health insurance for all retired Americans. It was favored by as many as 69 percent of the population in polling.

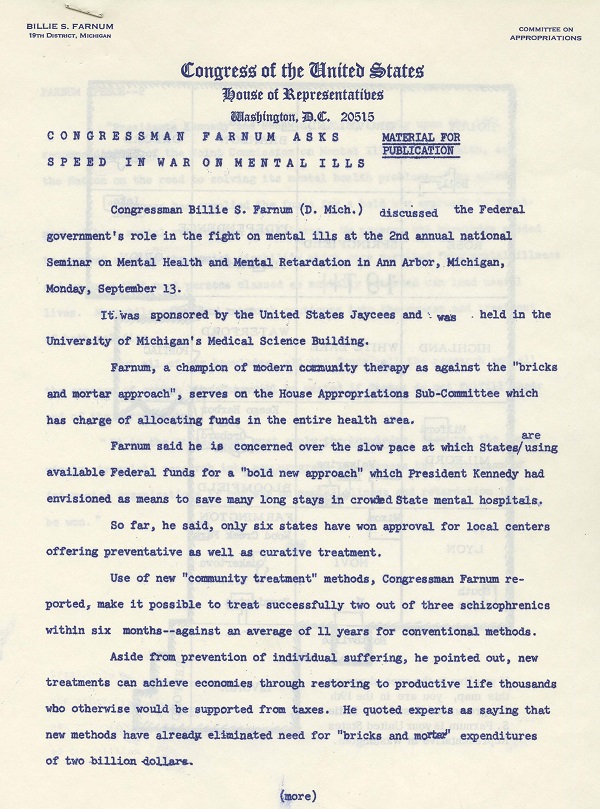

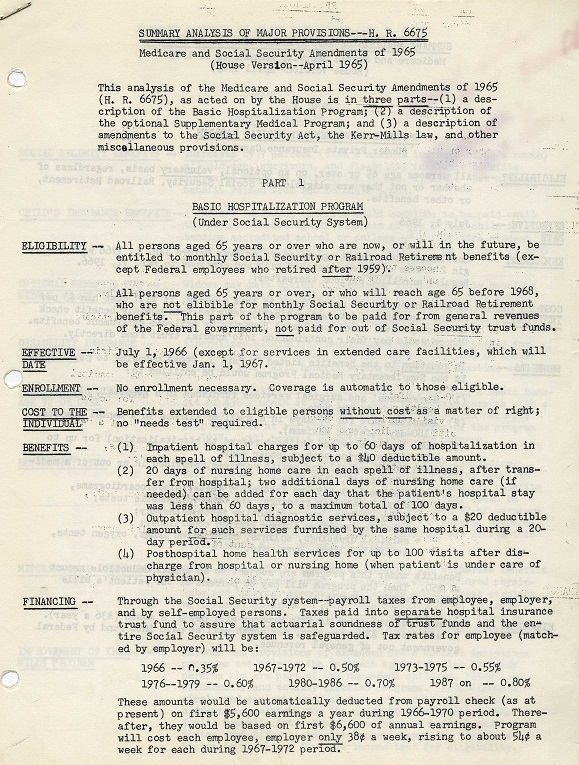

“Summary Analysis of Major Provisions – H. R. 6675,” April, 1965

(Box 6, Billie Farnum Papers, Oakland University Libraries' Special Collections)

This document is an internal description of the Medicare and Social Security Amendments of 1965. Those amendments created the Medicare program that is still in place today.

The document contains information intended to aid Farnum in explaining Medicare to constituents.

In its first iteration, Medicare had two major components. These consisted of a federal government pledge to fund basic hospitalization of Americans over 65, and an offer for optional federally-funded medical insurance for the same demographic. These documents were fact sheets to help explain this complicated program.

The Medicare debate

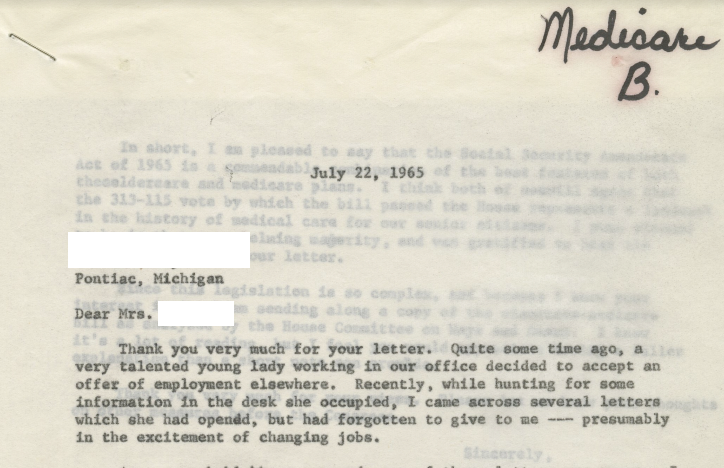

In another letter to a constituent in 1965, Farnum addresses (albeit with some typographical difficulties he blamed on a departing secretary!) some of the confusion surrounding the implementation of Medicare.

“Letter to constituent,” July 22, 1965

(Box 6, Billie Farnum Papers, Oakland University Libraries' Special Collections)

Farnum here responds to the American Medical Association’s claim that Medicare is “socialistic.” He asserts that the program is in fact an attempt to help Americans pay for their medical expenses.

Farnum claims that Medicare does not interfere in the operation of the free market in any way: it just adds federal money to the healthcare pool.

Farnum argues that opposition to Medicare was about framing, not content. The federal government, he said, was in fact merely providing incentives for retired Americans to look out for their health.

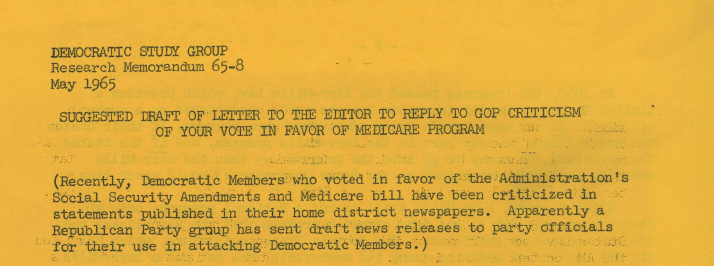

Criticism of Medicare and the Response from Democrats

Opposition to Medicare was well-coordinated. While about 50% of Republicans in Congress voted for the bill, the party's conservative wing opposed it.

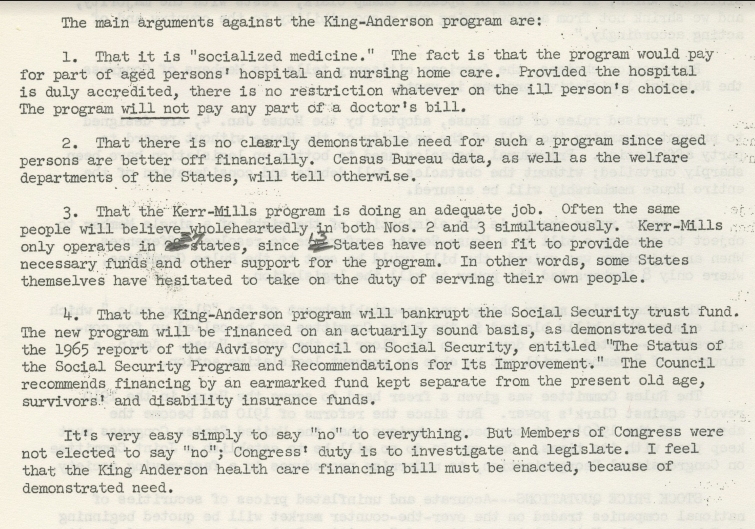

This Democratic Party strategy document from 1965 outlines the oppositional arguments.

“The main arguments against the King-Anderson program”(1965)

(Box 11, Billie Farnum Papers, Oakland University Libraries' Special Collections)

There were four main lines of attack on Medicare.

First, there was the familiar “socialized medicine” accusation.

Second, there was the assertion that most Americans already had insurance.

Third, there was an argument that state programs were already doing the job for which Medicare was designed.

Lastly, some Republicans claimed that Medicare would bankrupt Social Security.

As shown here, Democrats prepared arguments to refute these attacks. These responses were successful with the public. Few people today assert that there is no health benefit for subsidized healthcare. Nor is it common to argue that state programs are providing adequate health care on their own. Even the framing of government healthcare as "socialized medicine" has largely disappeared.

Medicare and Michigan Seniors

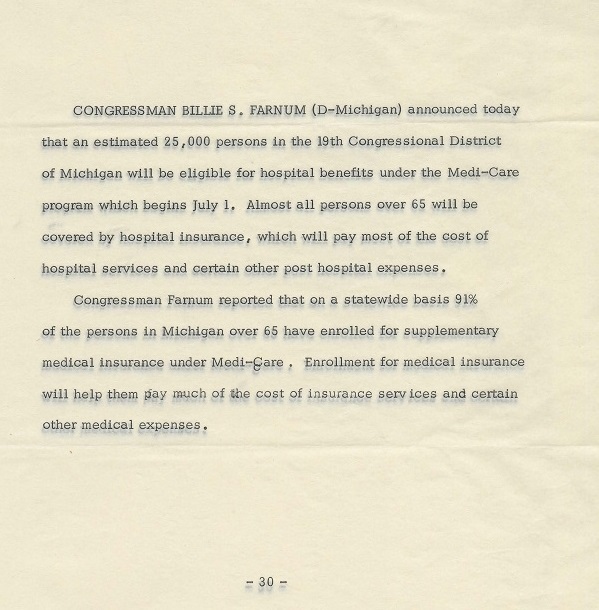

“Bio,” [1965 probable]

(Box 14, Billie Farnum Papers, Oakland University Libraries' Special Collections)

In this press release from June, 1965, Farnum notes how Medicare will affect the 19th District.

Medicare was popular with senior citizens in Michigan. As the document notes, 91% of them enlisted in Medicare to some degree. 25,000 senior citizens who previously did not have insurance in the 19th District did because of the program.

Medicare was well-received both within the district and nationally. This was in large measure because all Americans would, in theory, be eligible for it at some point regardless of income. Medicare also restricted its aid largely to the elderly, who were perceived with overwhelming sympathy within the culture.

Mike Rogers and Health Care Reform in the Bush Presidency

Michael J. Rogers (born 1963) was the Republican congressman for Michigan’s 8th US House district from 2001 to 2015.

After serving in both the U.S. Army and F.B.I., Rogers started his political career in the Michigan Senate. He won his U.S. House seat in a famously close election decided by 111 votes.

Rogers made his name in the US Congress on national security issues. Eventually, he was appointed to lead the important and prestigious House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence.

Upon his arrival in the U.S. House of Representatives in 2001, health care reform was a prominent part of Mike Rogers’ plans.

This was because of the consistent popularity of expanding Medicare with the public and politicians alike. After the 1960s, Medicare became a bipartisan issue.

Rogers' interest was also due to the continued failings of the American health system. President Ronald Reagan and the Congress of the 1980s took steps to cut costs. They set limits on what services the government would cover.

But both parties embraced Medicare expansion in the 1990s. The bipartisan support for Medicare, and increasing acceptance of government intervention in health care, was due to the decreasing reliability of employer health care plans and the increasing cost of health care services.

Reforming Medicare

In the early 2000s. Medicare did not cover prescription drugs or “care management.” (Care management refers to addressing health problems before they become serious).

“The State News Questionnaire,” October 17, 2000, Floppies

In this answer to a news outlet Rogers outlines his plan to reform Medicare. Rogers notes that the original 1965 program needs to be updated for the 20th century.

He argues that technological advances could potentially cut costs in treatments. Ironically, an agency existed to keep track of these possibilities until the 1990s. It was, however, eliminated by the Republican-controlled Congress.

Prescription drug coverage options, however, were a genuinely new development. They reflected the early 2000s Republican agenda, which aimed to improve the quality of healthcare for seniors and decrease costs.

The Expansion of Medicare into Prescription Drugs

Republicans endeavored to create a new component to Medicare. President George W. Bush made prescription drug coverage in Medicare a major part of his agenda in his first term in office. It passed along partisan lines, with few Democrats voting yes.

Passing Medicare part D was a major achievement for President Bush. It was extremely popular with the public.

In this letter to a constituent, Rogers explained the Republican approach to cutting down prescription drug costs (known as Medicare Part D).

“Letter to a constituent,” August 7, 2001, Box 30, Michael J. Rogers Congressional Collection

Rogers noted that the reforms in Medicare Part D provide senior citizens with a prescription drug discount card. He argued that this is a “first step” toward aiding Americans over-65 in paying for skyrocketing prescription drug costs.

Use of Health Savings Accounts to Cut Health Care Costs

One option favored by Republicans in Congress, as well as President Bush, in the early 2000s was the so-called Health Care Savings Account (HSA).

Individuals signing up for a Health Care Savings Account are allowed to make tax-deductible deposits into the account. They can then withdraw money when they have a health crisis.

Rogers and others favored HSAs for putting the responsibility for healthcare in the hands of patients.

“Lansing State Journal Questionnaire (lsj.wpd),” October 1, 2004, Floppies,

Michael J. Rogers Congressional Collection

In these excerpts from a media questionnaire, Rogers explains his interest in HSAs and why he believes they and other healthcare reforms are necessary.

It was little remarked upon at the time that HSA's actually go a step further than Medicare in some ways. They attempt to reduce healthcare costs for all Americans rather than only senior citizens. Their existence, and Republican support for them, is indicative of the sheer scope of the health care crisis facing the United States.

HSAs were also indicative of the favored Republican approach to healthcare in that decade. Democrats wanted to provide direct subsidies to vulnerable populations (like seniors). Republicans sought to provide indirect subsidies in the form of tax breaks.

Criticism of HSAs and the Republican Response

Health Savings Accounts were and are contentious. They require a significant investment in time to research and manage on the part of consumers. The unpredictable nature of healthcare needs can mean that reliance on an HSA could be inadequate in the face of a large expense. This is particularly the case if a patient has no other source of funds.

Proponents of HSAs, meanwhile, emphasize that HSAs have low premiums. HSAs can also be kept if an individual switches jobs or becomes unemployed, and make patients more aware of the costs of health care.

Republicans prepared arguments to refute their political opponents.

“Marcinkowski Attacks Versus the Facts,” October 20, 2006, Box 2,

Michael J. Rogers Congressional Collection

Here, in a campaign advertisement, Rogers counters arguments by his 2006 opponent Jim Marcinkowski. Marcinkowski charged that HSAs were only useful for the wealthy.

Private Market Solutions

While Rogers favored expanding Medicare, he was a firm believer in the basic efficacy of the free market in healthcare.

He thought that the employer-based healthcare system worked for the general population. As illustrated in this letter to a constituent, Rogers thought that competition protected against abuses by medical practitioners.

“Issue Mail: Health Insurance Premiums,” August 17, 1998

Box 30, Michael J. Rogers Congressional Collection

In the document below, Rogers explains he wants to give tax breaks to businesses that provide healthcare plans to their employees. He believed such indirect subsidies would reduce healthcare costs.

“Document, re: Rogers Nurses Association Questionnaire,” August 9, 2000,

Michael J. Rogers Congressional Collection

Protecting Consumer with a Patient's Bill of Rights

In response to the growing opacity of the insurance market, one popular means of providing greater transparency and protections for consumers was a so-called Patient Bill of Rights.

This was a bipartisan bill authored by Michigan’s John Dingell and Iowa’s Greg Ganske. The bill, passed in 2001, regulated the relationship between patients, doctors, and insurance companies.

It strove to create greater transparency in health care and avoid insurance company exploitation.

Rogers supported this bill, which was a rare example of bipartisan health care legislation in the early 2000s.

“Issue mail: Patients’ Bill of Rights,” July 16, 2001, Box 30,

Michael J. Rogers Congressional Collection

Conclusion

Healthcare is more expensive in the United States than in any other wealthy nation.

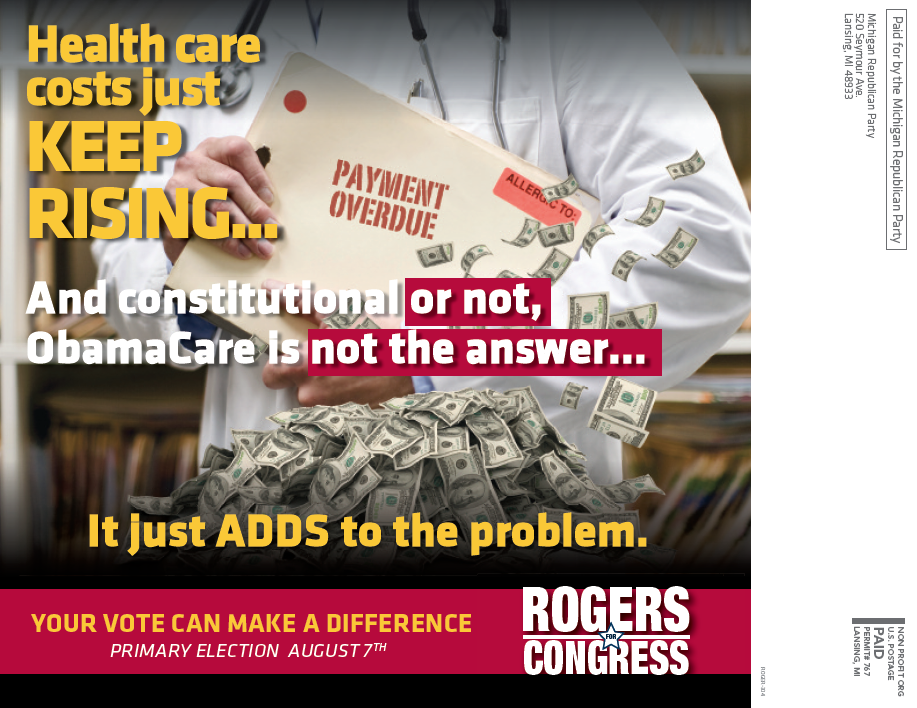

Rogers for Congress postcard about protecting pedatric medicine, 2012

(Michael J. Rogers Congressional Collection)

Both Republicans and Democrats have acknowledged this for sixty years. Each has advocated for employing the federal government to reform the way health insurance works in this country.

Disagreements were over the means of manipulating the healthcare market, not about the desirability of doing so.

Democratic Study Group Research Memo, "Suggested Draft of Letter to the Editor to Reply to GOP Criticism of Your Vote in Favor of Medicare," May 1965 (Billie Farnum Papers)

Democrats sought to provide subsidies to patients directly. This approach eventually resulted in the Affordable Care Act in 2009.

Republicans, meanwhile, indirectly gave subsidies to the providers of care. Sometimes their bills gave subsidies to employers, other to physicians. These subsidies were generally in the form of tax cuts.

Rogers for Congress postcard against Obamacare, 2012

(Michael J. Rogers Congressional Collection)

Democrats like Farnum in the mid-1960s believed they could best fix healthcare by providing patients with the means of accessing quality healthcare directly. Universal healthcare was considered too drastic and expensive an effort. Accordingly, most Democratic initiatives aimed to target specific at-risk populations. These included seniors, the poor, and children, who were aided by Medicare and Medicaid.

Republicans like Rogers in the early 2000s, meanwhile, had a multifaceted approach. They thought that a targeted program like Medicare was too much a part of the fabric of American society to change. They also believed that providing funding to patients themselves was expensive and inefficient. They thought it far more effective to aid the practitioners of medicine and the employers who provided health plans.

Discussions over the Affordable Care Act and American Health Care Act have been heated and divisively partisan. It is important to recognize, however, that both parties have engaged in the healthcare conversation of the last 60 years.

No party has a monopoly on employing government intervention to ease healthcare costs for Americans. On the contrary, the impetus to fix healthcare has been a rare unifying policy throughout the bulk of modern American history.

Sources

Barabas, Jason. “Not the Next IRA: How Health Savings Accounts Shape Public Opinion,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law 34 no. 2 (April 2009).

Brown, Lawrence D., and Michael S. Sparer. “Poor Program’s Progress: The Unanticipated Politics of Medicaid Policy,” Health Affairs 2 no.: 1 (January 2003).

Daschle, Tom, and David Nather. Getting It Done: How Obama and Congress Finally Broke the Stalemate to Make Way for Health Care Reform. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2010.

Grogan, Colleen, and Eric Patashnik. “Between Welfare Medicine and Mainstream Entitlement: Medicaid at the Political Crossroads,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law 28 no. 5 (2003).

Hughes, Dana, and Mary Keger, Simran Sabherwal, Darci Powell, and Katherine Sargent. “Universal Health Insurance for Children,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 20 no.:1 (February 2009).

Leonhardt, David. “Republicans and Medicare: A History,” New York Times (October 20, 2010).

Levitsky, Sandra R. “What Rights? The Construction of Political Claims to American Health Care Entitlements," Law & Society Review 42 no. 3 (September 2008).

Oberlander, Jonathan. “The Political History of Medicare,” Generations (Summer, 2015).

Weeks, Lewis E., and Howard J. Berman. Shapers of American Health Care Policy: An Oral History. Ann Arbor, Mich: Health Administration Press, 1985.

Weissert, Carol S., and Malcolm L. Goggin. “Nonincremental Policy Change: Lessons from Michigan’s Medicaid Managed Care Initiative,” Public Administration Review 62 no. 2 (March/April, 2002).

In providing access to its collections, the Oakland University Archives and Special Collections acts in good faith. Despite the safeguards in place, we recognize that mistakes can happen. If you find on our website or in a physical exhibit material that infringes on an individual’s privacy, please contact us in writing to request the removal of the material. Upon receipt of valid complaints, we will temporarily remove the material pending an agreed solution.