The Pontiac Oral Histories collection at Oakland University

In Fall 1975 Johnetta Brazzell, then director of community programs for Oakland University's Urban Affairs Center, launched an oral history project to document life in Pontiac’s Black community before World War II. Among the interviewees were Thomas C. Holland, father of then Pontiac mayor Wallace Holland, and Nellie Ryder, who was the first black student to graduate from Pontiac High School in 1917 and was active in the Newman Methodist Church, the first black church in Pontiac. The collection paints a unique view of the growth and challenges of the Black community in Pontiac before the war.

Johnetta Brazzell

Johnetta Brazzell was hired as director of community programs at the Oakland University Urban Affairs Center in 1973, under the direction of Wilma Ray-Bledsoe. Established in 1968, the Center’s mission was to develop new curricula dealing with racial issues, to create new programs to support disadvantaged minorities on campus and to strengthen relations with nearby communities, especially Pontiac. Brazzell was promoted to director of the Urban Affairs Center and then became director of career and placement services. She stayed at OU until 1987.

Johnetta Brazzell in 1981

With a B.A. in history and political science from Spelman College and an M.A. in American history from the University of Chicago, Johnetta Brazzell had come to Michigan with her husband in 1972. Her master’s degree had an emphasis on the African-American experience and she participated in the development of new Black and African studies at OU, co-teaching history courses with Professor DeWitt Dykes.

Free to manage community outreach programs as she pleased, she was involved in several significant projects at OU. She developed connections with many individuals and organizations in Pontiac and started an oral history program. She organized workshops to prepare women going into business in Detroit. She also served on the board of the new African American museum in Detroit - which was at the time, an all volunteer force housed in a small house, who did everything themselves.

For her accomplishments, she was selected as Outstanding Young Woman for 1978.

She left OU in 1987 to get a PhD degree in higher and adult continuing education at the University of Michigan. Her dissertation focused on the history of higher education for Black women -- a topic she would continue to research her entire career. She went on to have a brilliant career in higher education administration. After a position as Associate Dean of Students and interim Dean at the University of Arizona, she became Vice-President of Student Affairs at Spelman College in 1993 and in 1998 Vice Chancellor of Student Affairs at the University of Arkansas, where she stayed for 10 years until her retirement.

She was a Fulbright scholar and served in many roles for professional organizations and educational and community boards, like the Georgia Commission for National and Community Service, the Higher Learning Commission NCA Board of Trustees, and as chair of the National Advisory Committee for Minority Undergraduate Fellowships Program, part of the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators (NASPA).

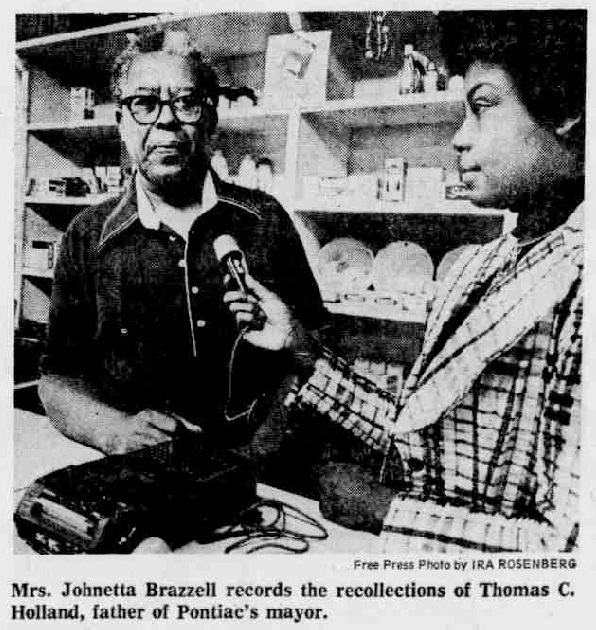

Johnetta Brazzell interviews Thomas C. Holland, long time resident of Pontiac

Johnetta Brazzell interviews Thomas C. Holland, long time resident of Pontiac (newspaper clipping - Detroit Free Press, October 18, 1975; 5)

The Pontiac oral histories project

While at OU, Johnetta Brazzell was particularly interested in the history of Black migrations to Michigan from the South in the 1920s-1940s period, and Pontiac had many residents who had been part of those historic population movements. Attracted by manufacturing jobs and the economic growth of the area, those men and women had contributed to the growth of the Black population in Pontiac.

In the early 1970s, historians were increasingly interested in oral histories as a way to record the experiences of ordinary Americans -- factory workers, small business owners, professionals, families, and more. For Brazzell, it was vital to document the lives of Black Pontiac residents, because, as she put it, “oral history is the only account anyone has” of those lives.

She joined the Oral History Association and learned how to produce her own oral histories. She started the Pontiac oral histories project in Fall 1975. Armed with a tape recorder, she went out to interview Black Pontiac residents in their own homes or businesses. She also enlisted students from a class she and Professor DeWitt Dykes were teaching.

Thus, Brazzell recorded Thomas C. Holland’s story at his grocery store, on the south side of Pontiac. Interviewees talked about their jobs and working conditions, the labor movement, the local housing situation, the segregation they suffered, politics, schools, churches, and all aspects of their lives.

Clipping from “Those who were there write ethnic history,” Detroit News, October 10, 1975

Clipping from “Those who were there write ethnic history,” Detroit News, October 10, 1975In 1976, Johnetta Brazzell obtained a $2,000 grant from the Oakland County American Revolution Bicentennial Commission and $600 from the Pontiac Bicentennial Committee to continue the interviews. She envisioned a larger project that would include other racial and ethnic minorities.

Oakland University fully supported her project. According to OU President Don O’Dowd, “If older people are led to believe that their memories are no more than nostalgic remnants, important pieces of history may never be recorded.”1

However, for lack of funding, the interviews ended a couple of years later.

By then Brazzell and her team had recorded 39 interviews, which are now housed at the Oakland University Archives and Special Collections in Kresge Library. Some of the cassette tapes have been digitized, and transcripts are available for a few recordings.

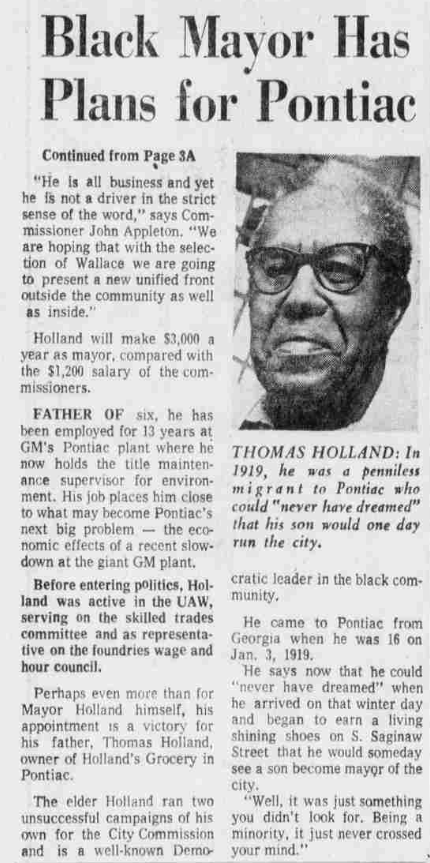

Thomas C. Holland

Brazzell noted that her interview of Thomas C. Holland may have been “the most fruitful.” Holland was the father of then Pontiac mayor Wallace Holland and had himself been very active in local politics.

Thomas C. Holland in 1992 (seated, left)

Thomas C. Holland in 1992 (seated, left)with former volunteers of Les Hudson’s 1958 campaign for Congress

(Photographed by Amy E. Powers, Oakland Press)

Born in Georgia in 1901, Holland came to Pontiac in 1919. He worked at the O.J. Beaudette plant that made bodies for Ford’s Model T’s, other auto plants, and a variety of WPA jobs during the New Deal. In his interview, he describes working conditions, housing, schools, churches, clubs, unions, and more for the growing black community in Pontiac from the early 1920s through the Great Depression and war.

He also addresses the state of racial relations and the challenges faced by Blacks, from work discrimination to the Bullet Club -- a secret organization that was the political action arm of the far right vigilante Black Legion in the 1930s.

Some excerpts from Holland’s interview:

“When you come from an area of the country where politics is denied to you, you don't just come in and grab it and pick it up. I lived through that. “

“...back out at Fisher Body, they wouldn't even take a black out there in '29 when they moved out there. My son been out there 17, 18 years now. “

“So this white worker with me said let's stop in here and get us something to eat or something to drink or something… Well, I guess he hadn't been here as long as I had. I had seen the change, see…. so we go into a restaurant. The girl comes. That was right up on Huron Street ... So she says, "We can serve you," talking to him, see, "but we can't serve him…. I was his boss but they're gonna serve him, but they wasn't gonna serve me. I was his supervisor! … I could show you just how, how cruel it is and how warping it is to the mind of white or black when he gets hate or bitter discrimination in his mind. “

“There's something about freedom that makes you relax. ...crisis brings men together. It brings men together. You plot a new course. He may stray from you later, but you and him will walk side by side for a while in that new course. That's why being in the union, we walk side by side. Side by side. Now we've strayed a little.”

Detroit Free Press, January 7, 1974 article about

Detroit Free Press, January 7, 1974 article about Thomas Holland’s son, Wallace Holland, becoming Pontiac’s first black mayor.

For more information

Pontiac Oral History collection, Oakland University Archives and Special Collections.

Tish Myers, "Those Who Were There Write Ethnic History," Detroit News, Nov. 10, 1975, 4C

Oakland University Board of Trustees Minutes, April 28, 1976

Timothy J. McNulty, "Oakland Blacks Put History on Tape," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 15, 1975, 1A

Interview of Johnetta Brazzell, in Remembrances in Black, eds. Charles F. Robinson II and Lonnie R. Williams (University of Arkansas Press, 2015), 250.

Text by Dominique Daniel.

All images courtesy of Oakland University Archives and Special Collections.

1President O’Dowd to J. Brazzell, June 8, 1977, O’Dowd Papers box 3, folder “Johnetta Brazzell” (Oakland University Archives)