Issues

Casinos

Legal gambling establishments, once confined to scattered enclaves across the United States, began to become prevalent throughout the country after the passage of the 1988 Indian Gambling Regulatory Act. Throughout his career, Rogers opposed the expansion of legalized gambling due to his belief that casinos bred crime in surrounding communities. In both the Michigan Senate and U.S. House of Representatives, he argued that casinos increase crime, bankruptcies, suicide, and family costs. This was an antithetical agenda to that of many of his fellow Michigan representatives. In 2003, the Republican delegation in the House split over the attempt to construct Indian casinos in Vanderbilt, Romulus, and Port Huron. Whereas Rogers fought against the expansion of gambling in those cities, Democrat John Dingell and Republican Candice Miller were strong proponents for the casinos. In 2006, Rogers called for a two-year moratorium on new tribal casinos in the United States. “With 223 Indian tribes operating 411 casinos in 28 states and bringing in more than $18 billion in revenue annually, there is just too much money involved and no way to fully account for it,” he said (Detroit News, January 10, 2006). When the moratorium expired in 2008, Rogers made an unlikely but successful alliance with Democratic representatives John Conyers and Carolyn Cheeks Kilpatrick to again block the Romulus and Port Huron casinos.

Environment

.jpg)

Rogers touring the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality in 2002.

The Michigan environment was frequently under threat in the 1990s and 2000s, and Rogers was a participant in many of the ensuing battles. Rogers’ position, in general, was that the environment should be protected so long as regulations did not endanger the activity of businesses or the sovereignty of the states: a belief that earned him the ire of environmental advocacy groups even as he often argued for state and federal funds for conservation efforts. He spearheaded the Clean Michigan Initiative in 1998, which provided hundreds of millions of dollars in funding for cleaning up and redeveloping urban sites, lakes, and rivers, and for preventing future pollution. He also engaged in a long battle against the importation of Canadian trash into Michigan landfills. Rogers introduced measures into the U.S. House of Representatives nearly every year designed to halt the Michigan state government, which Rogers argued did not have the authority to regulate foreign waste, from selling space in its landfills for Canadian trash. Congress as a whole, however, worried that the ban would be illegal under the North American Free Trade Agreement, and none of Rogers’ attempts to create a prohibition against importation made progress toward becoming law (despite some bipartisan support for Rogers’ efforts). The importation of Canadian trash was ultimately stymied by an agreement between the United States and Canada in 2006.

In 2001, however, Rogers opposed the federal moratorium on oil and gas drilling in the Great Lakes, arguing that it was a state issue. Rogers argued that “This is about Congress going into the Great Lakes states and saying, “You don’t know what you’re doing” (The Blade, June 29, 2001). Rogers instead echoed the Bush administration in asserting that the states should decide whether the Great Lakes have drilling. He alleged that the ban opened the door for more federal control over the Great Lakes, which he contended was “a very, very dangerous step” (USA Today, November 1, 2001).

Beginning in 2010, Rogers, with much of the rest of the U.S. House delegation from Michigan, argued against the importation of Asian carp into the Great Lakes, asserting that Asian carp were an invasive species that would do ecological damage. “The potential consequences of failing to prevent the infiltration of Asian carp could prove disastrous not only to the thriving Great Lakes ecosystem, but also to the booming Great Lakes economy that relies on a healthy fishing industry that is valued at $7 billion on the U.S. side alone,” Rogers claimed (Targeted News Service, August 3, 2012).

Healthcare

In the 1990s and 2000s, the cost of healthcare was an important issue. Though Hillary Clinton’s proposed 1993 health care plan, the Health Security Act, was defeated in Congress, few Americans doubted that they were paying too much for healthcare. There were many proposed and enacted reforms. Many ideas were suggested, both on a state and federal level, in the next decade regarding how to cut down health costs for most Americans. Rogers believed that, while healthcare should be reformed, it should be through measures that encourage free market solutions. Mike Rogers was in favor of so-called “health care savings accounts,” which allowed insured Americans to make tax-free contributions to their future health costs. Rogers ran for Congress, in part, on a platform that emphasized the necessity of health care savings accounts for the reduction of costs. Health Care Savings Accounts became a part of Medicare by law in 2003. When George W. Bush proposed incentives for the uninsured to purchase health insurance in 2006, Rogers supported his measures. “He’s applying the free market and expanding what we know is starting to work,” Rogers said (Kalamazoo Gazette, January 31, 2006). Rogers also cosponsored a bill that would have created a national electronic database and information-sharing system for hospitals and physicians.

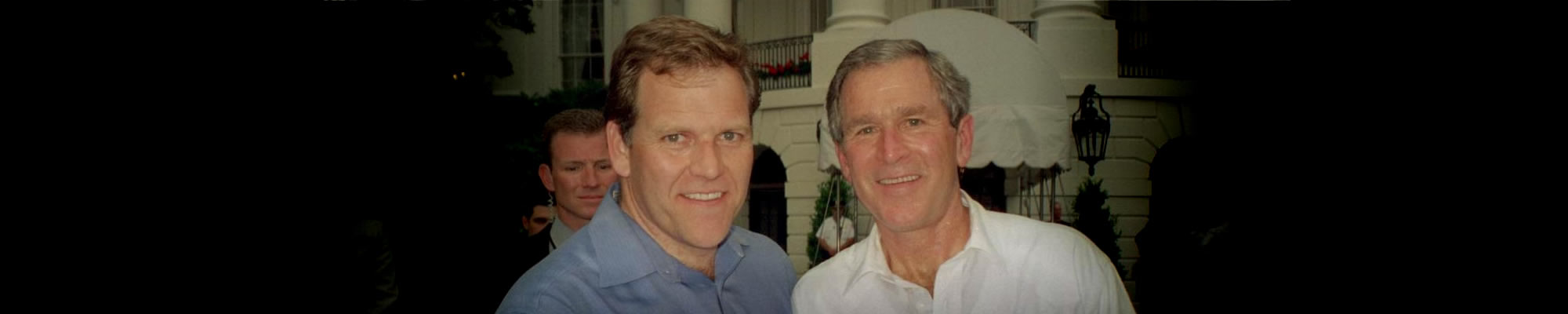

Rogers heavily opposed President Obama’s regulation of healthcare by the federal government. After the Affordable Care Act became law in 2010, Rogers was among the many Republicans who attempted to repeal it. “While Michigan continues struggles to create jobs, the only jobs this health care bill will create are at the IRS… We can all agree that America needs health care reform but this is the wrong way to do it,” Rogers asserted. He contended that the Affordable Care Act passed health care costs on to employers, who would be forced to lay off workers and increase prices as a result.

See the online exhibit Making Health Care Affordable: 50 Years of Health Care and the U.S. Congress, showcasing items from the Michael J. Rogers Congressional Collection and the Billie S. Farnum Papers.

National Security

.jpg)

Rogers meets Afghani president Hamid Karzai in Afghanistan on a fact-finding mission (2002)

Rogers rarely discussed national security issues before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Afterwards, national security became an intrinsic part of his platform. For Rogers, 9/11 changed everything, necessitating revisions in foreign policy, civil liberties, and criminal justice. “This is as close to a declaration of war on the United States as you can get… But I’ll tell you, any country that harbors a criminal that can do this to innocent men, women, and children, I’m sorry, I’m not going to shed a tear if we extract justice,” he said in the immediate aftermath. Rogers was a supporter of the Patriot Act and, as a former FBI agent, was consulted during the authoring of the bill’s provisions. Rogers advocated stricter regulation of communications in the United States in order to better anticipate terrorist acts. He argued, “Technology has changed… The law is not written to keep pace with the technology improvements of today, and the way terrorists operate.” He also had a role in the bill’s alterations on illegal immigrant detention facilities and facilitating the flow of intelligence.

Yet, Rogers had initial reservations about the prospective US operations in Iraq but he eventually supported “Operation Iraq Freedom,” the 2003 American intervention in that country. He advocated frequently for more funding and continued engagement even as the war became unpopular among Americans. Rogers wanted to maintain U.S. troop levels in Iraq because he was particularly concerned about the prospect of Iraq falling into anarchy after the successful U.S. operation. As early as late 2003, Rogers noted that security had deteriorated markedly due to an infusion into the country of foreign terrorists. “They’re coming there because a free Iraq… is a serious blow to autocratic terrorist organizations around the world, and they know it,” he opined (Ann Arbor News, September 6, 2003). In 2006, when many Democrats were arguing for a reduced American role in what had become an intense and bloody conflict, Rogers resisted. “We’ve seen progress – not as fast as we’d like, but we shouldn’t get up and say we’re going to withdraw troops,” Rogers claimed (Ann Abor News, October 6, 2006).

Rogers was in favor of a strong U.S. foreign policy on other national security issues, as well. President Obama campaigned in 2008 in part upon the necessity to close the American Guantanamo Bay detention facilities in Cuba due to violations of the human rights of suspected terrorists there. But Rogers urged that the base remain open, cautioning that Guantanamo Bay prisoners were unsuited to mixing with the populations of domestic prison facilities in the United States. “These are people who are psychologically conditioned to commit murder to go to heaven… They bring a whole range of training with them… You worry about them radicalizing the other prisoners,” he said (Newsmax, August 7, 2009). Rogers also protested against the Obama administration’s overtures toward Iran, and argued that Chinese cyber spying constituted an “intolerable level” of economic espionage (Agence France-Presse, October 4, 2011).

While Americans as a whole became decreasingly willing to support military intervention abroad in the 2010s, Rogers remained committed to an aggressive American foreign policy until his retirement from Congress. He supported the Obama administration’s air strikes on Libya, claiming that troops on the ground would have been “the wrong decision,” though he was skeptical of the Obama administration’s failure to consult Congress on the matter (NPR, March 28, 2011) He railed against President Obama’s reluctance to involve American forces in Iraq against the Islamic State in 2014, arguing that “You’re not going to humanitarian-aid ISIS out of Iraq and Syria.” Rogers called Obama’s initial inaction a strategy in itself, and a poor one: “This is a decision. That is policy, That is a strategy… And it’s not working” (Newsmax, August 31, 2014).

Internet Crime

In 2000, Mike Rogers' office sent an advisory to parents on internet crime

In the 1990s, much of the American public perceived the internet as a kind of lawless frontier, where anonymity and distance meant that United States law did not apply to activity online. Rogers spent much of his time in the Michigan Senate attempting to regulate the internet and protect consumers and vulnerable users (particularly children) from exploitation. He introduced several bills during his second term imposing punishments upon online criminal behavior, including for those who stalk and harass children, people who disseminate information online regarding bomb manufacturing, and against online gambling. In 2000, he championed a bill that would require libraries to restrict the ability of children to access pornography online. Rogers was criticized for his bill’s failure to clearly demarcate the line between pornography and “safe” material. The ACLU, for instance, argued that existing technology would lead library filters to prohibit classic books such as James Joyce’s Ulysses and D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (Detroit News, February 17, 2000). The bill was nevertheless made Michigan law in September of 2000.

In 2012, distressed by U.S. intelligence leaks from the WikiLeaks organization and foreign and domestic hacking attempts of U.S. government data, Rogers and Dutch Ruppersberger spearheaded a bipartisan bill to create a voluntary network of data sharing that could help protect corporation and government computers alike. While the Cyber Intelligence Sharing and Protection Act had strong support in the House of Representatives, several iterations failed to make headway in the Senate. This was likely due to its superficial similarity to the deeply unpopular (with the public) Stop Online Piracy Act, another internet bill introduced the same year and widely construed as a threat to free speech.

Energy Independence

Driven by natural disasters and geopolitical conflicts (particularly in the Middle East), the international price of oil rose from $25 per barrel to over $147 per barrel between 2003 and 2008. This precipitated widespread fears in the United States of a growing energy crisis that would make established American standards of living unfeasibly expensive or even impossible. Mike Rogers rejected conservation strategies, such as a 2003 Republican attempt to raise mileage standards on cars, claiming this was “like trying to treat obesity by mandating smaller pants sizes” (Daily Camera, April 15, 2003). He was, however, a proponent of engaging alternative energy sources in order to achieve American energy independence from the unstable Middle East. In pursuing this vision, Rogers emphasized the carrot over the stick, crafting a bill lin 2006 that would provide cash grants to filling stations that sell ethanol gasoline blends.

In the next several years, he supported measures to regulate and research ethanol fuel and the distribution of ethanol. “Every step taken toward developing and expanding our distribution system for alternative fuels… takes America that much further away from depending on foreign oil,” he said (Associated Press, February 11, 2007). In 2008, he authored the American Energy Independence Act, which in his own words, “calls for using the technology we have today to invigorate innovation and engage all of our resources to produce American-made energy” (Washington Times, June 6, 2008). This comprehensive plan aimed to make the United States self-sufficient in energy by 2015. The bill made no progress in Congress because it was perceived by opponents as both too lenient on domestic oil corporations and unwilling to offer safeguards for the environment. Rogers remained a champion of a gradualist energy reform policy that could free the United States from dependence on foreign oil without crippling American corporations which produced traditional energy sources.