Thomas Jefferson, American Bibliophile

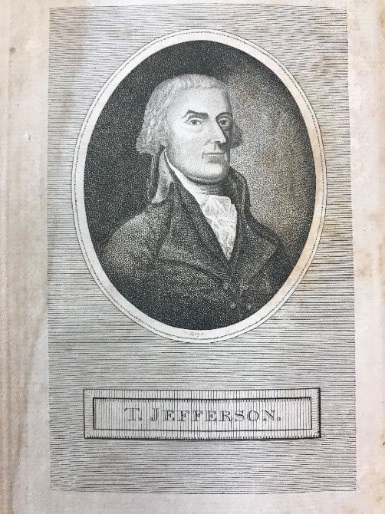

Thomas Jefferson by Mather Brown, 1786

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; bequest of Charles Francis Adams;

Frame conserved with funds from the Smithsonian Women's Committee

At the end of a letter to John Adams in 1815, Thomas Jefferson made a point to proclaim that he could not live without books.1 However, Jefferson, one of American history’s most learned intellectuals, only published one book in his lifetime. This work, known as the Notes on the State of Virginia, remains an important publication to both scholars of early American history as well as Americans interested in the intellectual capacity of one of its most famous homegrown thinkers. Jefferson was a prolific letter writer, conversing with scores of fellow men of letters throughout his life.

Within Oakland University’s archives and special collections are two important artifacts that pertain to the mind of Thomas Jefferson.

- One item is a letter written by Jefferson in 1798, when he was Vice President of the United States, to a book dealer in New York.

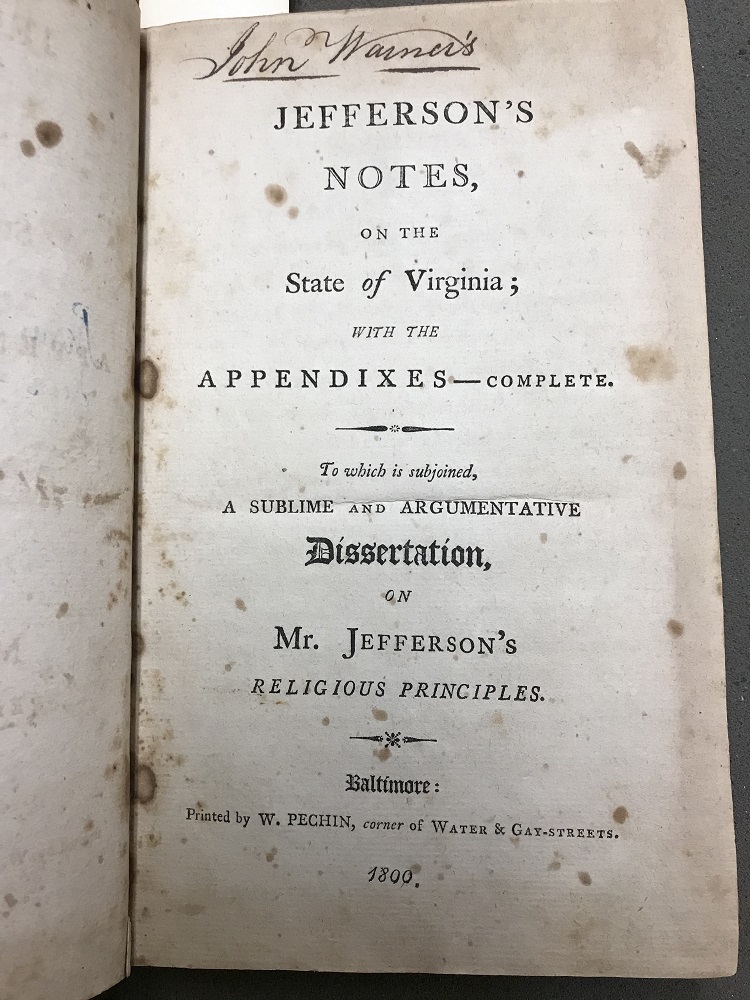

- The other artifact is an 1800 edition of Notes on the State of Virginia.

Both pieces are significant for their histories as objects and contain a surprising provenance, or record of ownership, throughout their lives as artifacts.

The Publication History of Notes on the State of Virginia

Inquiries from a Frenchman

In the middle of 1780, Francois Marbois, secretary of the French legation at Philadelphia, passed around a questionnaire among the Continental Congress requesting information on the various American states. The French government’s request came out of their greater involvement in the American Revolution and its outcome, in which they had become more politically and financially invested.Though the Virginia delegates were quite learned, they decided Thomas Jefferson, then governor of Virginia, was the best source of information for answers to Marbois’ questions. As author of the Declaration of Independence, amateur scientist, and expert on all things Virginia, Jefferson was indeed well suited to respond to Marbois. The answers that Jefferson formulated for Marbois would become the foundation for his only monograph, Notes on the State of Virginia.

Throughout 1780 and 1781, Jefferson invested a considerable amount of time and effort into his answers to Marbois. Despite the personal hardships that he had to face, including the death of one of his daughters, his wife’s declining health, and the war raging onto his own property, Jefferson always found moments to devote himself to the completion of his answers for the French delegate. At the end of 1781, Jefferson finally delivered his responses to Marbois.

“I now do myself the honour of inclosing you answers to the quaeries…I fear your patience has been exhausted in attending them…Even now you will find them very imperfect and not worth offering but as a proof of my respect for your wishes.” (Thomas Jefferson to Marbois, 20 December 1781)

Although Jefferson appears to criticize his own work, his willingness to circulate the manuscript among his friends and colleagues for “suggestions and corrections” contradict his expressed criticism of Notes. Fueled by his love affair with Virginia and his nearly unquenchable desire for knowledge, Jefferson devoted more effort still to the revision of the manuscript throughout the 1780s.2

Originally, Notes on the State of Virginia was to be for private use only. Jefferson sent out his personal copy to fellow learned men, only for the purposes of expanding and correcting the manuscript. As his manuscript made the rounds, more people became interested in its contents.

By spring 1784, Jefferson began to relax on the idea of circulating his manuscript and publishing his work, and he approached a bookseller in Philadelphia to meet this end. Unfortunately, the cost involved in printing the book was far too high for Jefferson. In the same year, however, Congress sent Jefferson to Paris to serve as Minister Plenipotentiary where he would negotiate treaties with other foreign nations, and he took his manuscript with him in hopes of finding a printer who could publish his work at a lower price.3

A Hot Commodity

After his arrival in France, Jefferson met French printer Philippe-Denis Pierres. Pierres agreed to publish Notes on the State of Virginia in English for a quarter of what it would have cost to print in Philadelphia. After making one last set of revisions, Jefferson turned in his copy to Pierres, and by May 1785, Pierres’ presses printed two hundred copies. Although this edition had some errors, including the wrong publication year, Jefferson was pleased enough with the copies that he circulated them privately. Jefferson did not want his book printed for the public because he believed this work would jeopardize support for both slave emancipation in Virginia and an alteration of Virginia’s constitution. In a letter to one recipient of Notes, Jefferson explained:

"The strictures on slavery and on the constitution of Virginia…I do not wish to have made public, at least till I know whether their publication would do most harm or good. It is possible that in my own country these strictures might produce an irritation which would indispose the people towards the two great objects I have in view, that is the emancipation of their slaves, and the settlement of their constitution on a firmer and more permanent basis." (Thomas Jefferson to Chastellux, 7 June 1785)

As more people requested to know the contents of Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson increasingly begged the recipients of his book not to pass it around. Eventually, one of the two hundred copies found its way into the hands of a French bookseller by the name Barrois, who intended on publishing an unauthorized French translation of the book to the public.4

Vexed by this obvious infringement on his rights as an author, Jefferson happily agreed to work with a respected French intellectual and recipient of his book named Abbé Morellet. With Morellet’s help, Jefferson could actually supervise a proper French translation of his work, or so he thought. Jefferson and Morellet’s partnership did not pan out so well due to their contrasting beliefs regarding the purposes of translation, and Jefferson was far from pleased with the outcome of this printing. He considered the 1787 French edition published by Morellet to be a “bad French translation,” and the book itself contained numerous errors, misprints, bad translations, and had been printed on poor quality paper with unpleasant type.5

Jefferson’s cherished intellectual project, once private but now released to the public in this mangled form, had turned into a complete nightmare. Not only were his ideas and arguments misrepresented in French but also this embarrassing edition could have inflicted serious damage on his reputation, of which he was quite protective.

Success at Last

Seeking a new and competent printer, Jefferson found English publisher and bookdealer John Stockdale. Jefferson requested that Stockdale print his queries “precisely as they are, without additions, alterations, preface, or any thing else but what is there.” Stockdale published an authorized English edition of Notes for Jefferson with such speed and skill that it only took him three weeks to print 1,000 copies.

By the summer of 1787, Jefferson had the pleasure of witnessing a suitable edition of his book for public consumption. Jefferson was so pleased with the outcome of the London edition that in September 1787 he planned to send it off to printers in the United States for public sale, and in 1788 the first American edition, which was a pirated copy of the Stockdale edition, was published in Philadelphia. The Stockdale edition of Notes is the copy that all subsequent editions of the book have been based upon.6

The Ordeals of Eighteenth-Century Publishing

The Inefficiency of Copyright Laws

Irksome to many intellectuals in this period was the problem of non-existent copyright laws, which did nothing to protect their rights as authors. For decades since the sixteenth century, English and American lawmakers passed copyright laws to protect printers, who were often booksellers and publishers, rather than authors and their ideas and arguments. In fact, printers had more of a financial stake than authors did in the outcome of the work. Publishers usually paid the author for their work in order to keep all rights to the book, or they paid the author a share of the profits, thus taking on the risk of the book’s failure or success. Regardless of any agreements made between author and publisher, authors could still expect unscrupulous publishers to pirate their books or pamphlets. Such was the case with Jefferson in Paris and Philadelphia, where his ideas were misrepresented with unauthorized and “mutilated” French translations, and the first American edition of Notes on the State of Virginia was pirated. Not until numerous authors lobbied their state and federal governments did the United States pass its first federal copyright law in 1790.7

Costs of Publishing

Jefferson’s issues with printers in Philadelphia and Paris were not only confined to author’s rights but included publishing costs as well. The high costs involved in financing the production of a book came out of the various expenses that publishers expected to pay including labor costs, paper, ink, and even the exorbitant personal expenses of their literary agents, or traveling salesmen. One example of the extraordinarily high prices attached to book publishing comes from a woman by the name of Hannah Adams, who published her dictionary of religions around the same time that Jefferson was trying to print Notes on the State of Virginia. Adams’s production cost came out to a hefty $510, a substantial sum in the eighteenth century. It was no wonder then that Jefferson sought out a cheaper printer in Europe, where the cost to publish a book was more affordable than in the United States. The prices that authors had to pay for book publishing were presumably passed down to yet another customer of the printer, the literate public.

Prices for Books

The cost to purchase a book in the eighteenth century was proportionally higher, perhaps even two to three times more, than it is to buy one today. Especially expensive were books on law, religion, and science, all of which Jefferson wrote about in Notes on the State of Virginia. In the early eighteenth century, one bestseller was worth about fifty pounds of tobacco. In another comparison, it was just slightly cheaper to buy a three-volume set of Don Quixote than it was to purchase four horses. If the American copy of the Stockdale edition of Notes cost as much as it did in London, at seven shillings, a day laborer in the United States would need to work, on average, three and a half days to afford Jefferson’s work. When compared to one pound of beef or a bushel of corn, both of which cost less than five shillings, the laborer would rather choose to put his pay towards sustenance.8

Treasures and Fortuitousness in the Archive

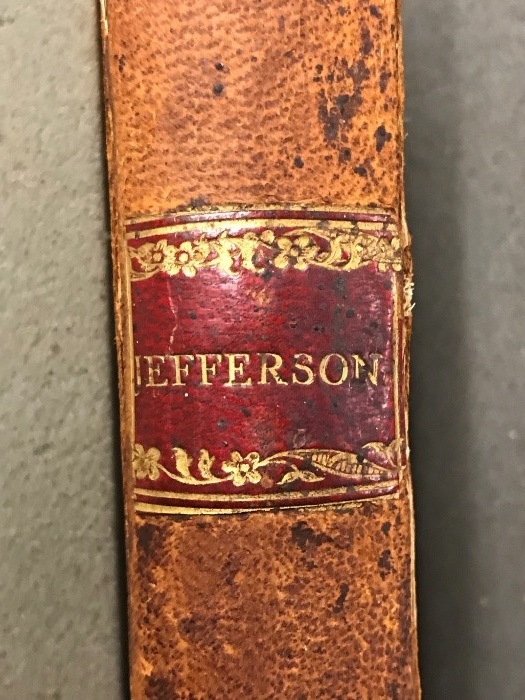

An 1800 edition of Notes on the State of Virginia

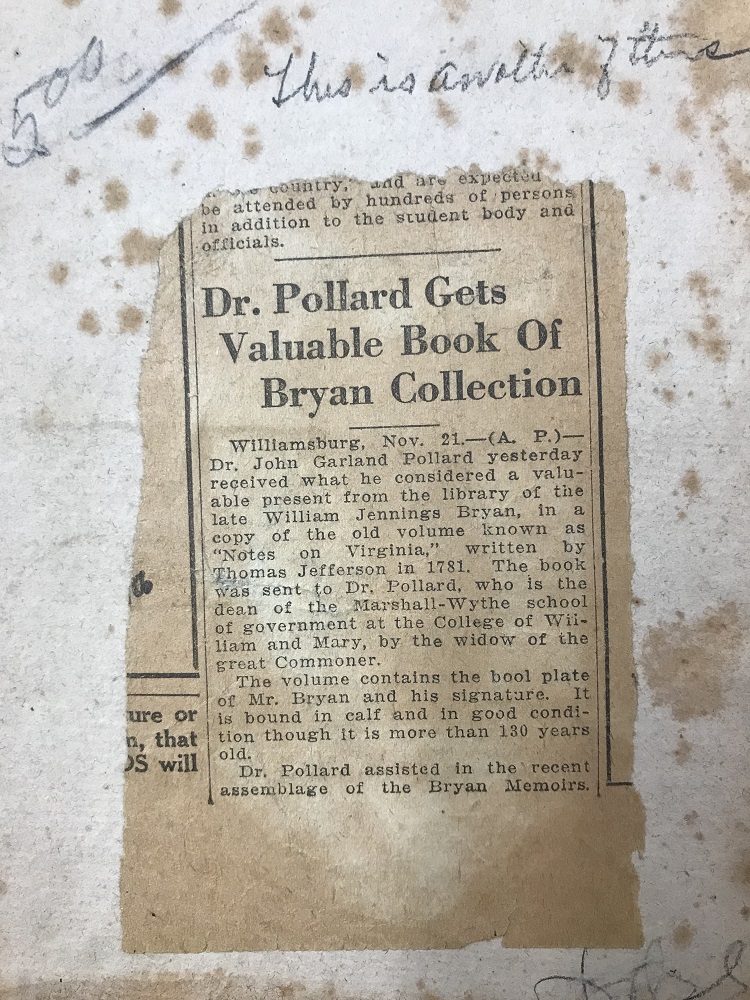

Oakland University’s archive does not hold a Stockdale edition of Notes, but it does have many of its earliest successors, including an edition from 1800. Scholars across generations have already analyzed the important contents and publication history of Notes, so it makes for a more interesting discussion when the material history of the archive’s 1800 edition is considered. The 1800 edition is a well-used, fragile copy that is bound in calfskin with a considerable amount of wear but still intact and readable. This particular copy also has what appears to be a distinguished provenance attached to it.

Pasted on the inside front cover of the copy there is an older newspaper article which recounts what is presumably one transfer of the edition. According to the article clipping, the copy belonged to famous populist, three-time Democratic presidential nominee, and former Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan. After Bryan passed, his friend and supporter Dr. John Garland Pollard received the book. Before Pollard accepted a position at the College of William and Mary as Dean of the Marshall Wythe School of Government, he served as Virginia’s Attorney General, and after his career at William and Mary became governor of Virginia.

However, even before Pollard and Bryan’s ownership, this particular copy of Notes belonged to a friend of Jefferson’s named John Warner, whose signature, expressing possession of the copy, resides at the top of the title page. John Warner was a West Indian (Caribbean) merchant from Wilmington, Delaware. He held numerous positions within government as well as important financial positions within Delaware including U.S. consul to Puerto Rico (1794-1816), U.S. commercial agent in Havana, Cuba, government bankruptcy commissioner, director of the Wilmington Bridge Company, director of the Bank of Delaware, and he was a member of the Delaware Abolition Society.9

The Vice President’s Letter

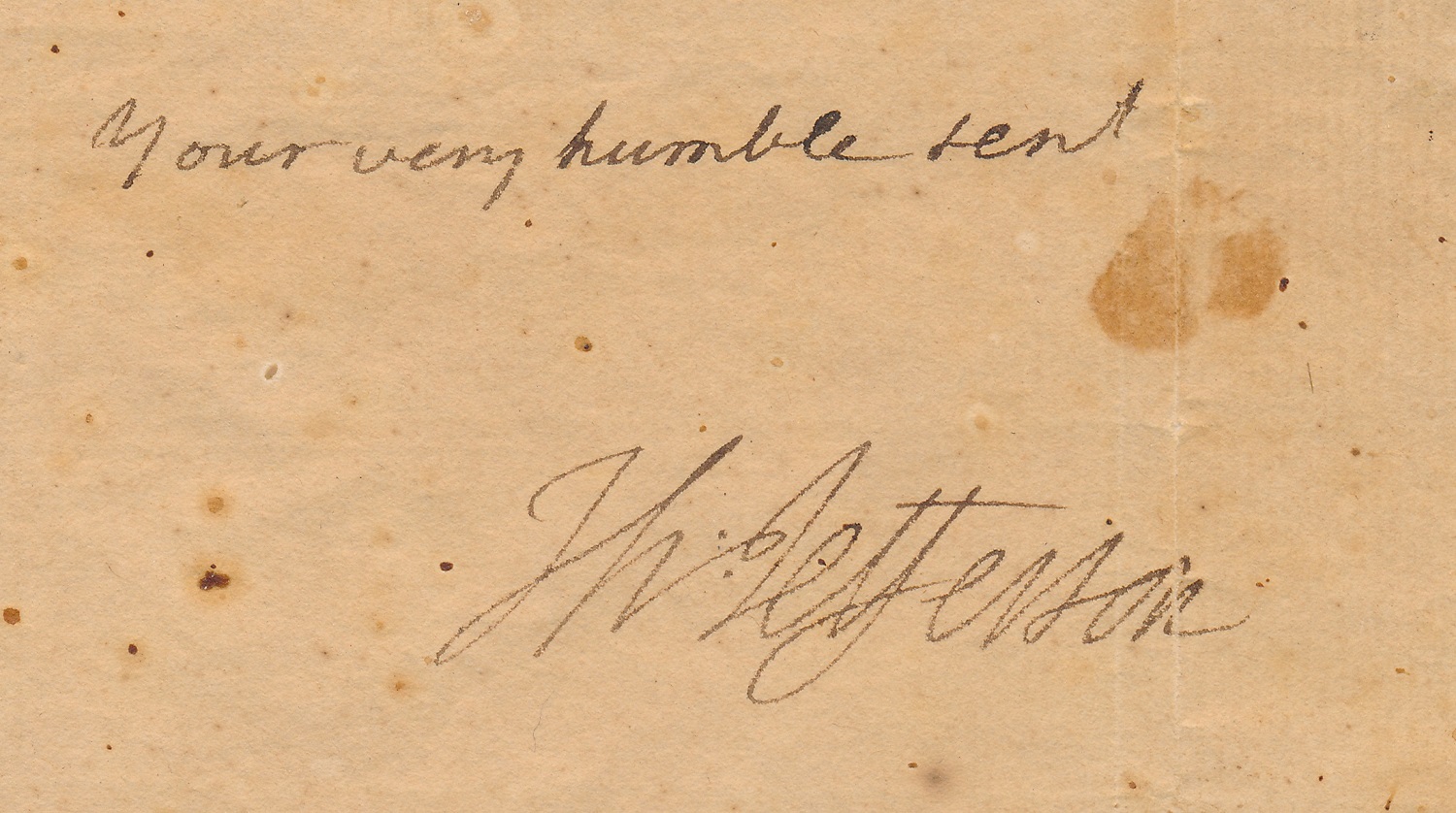

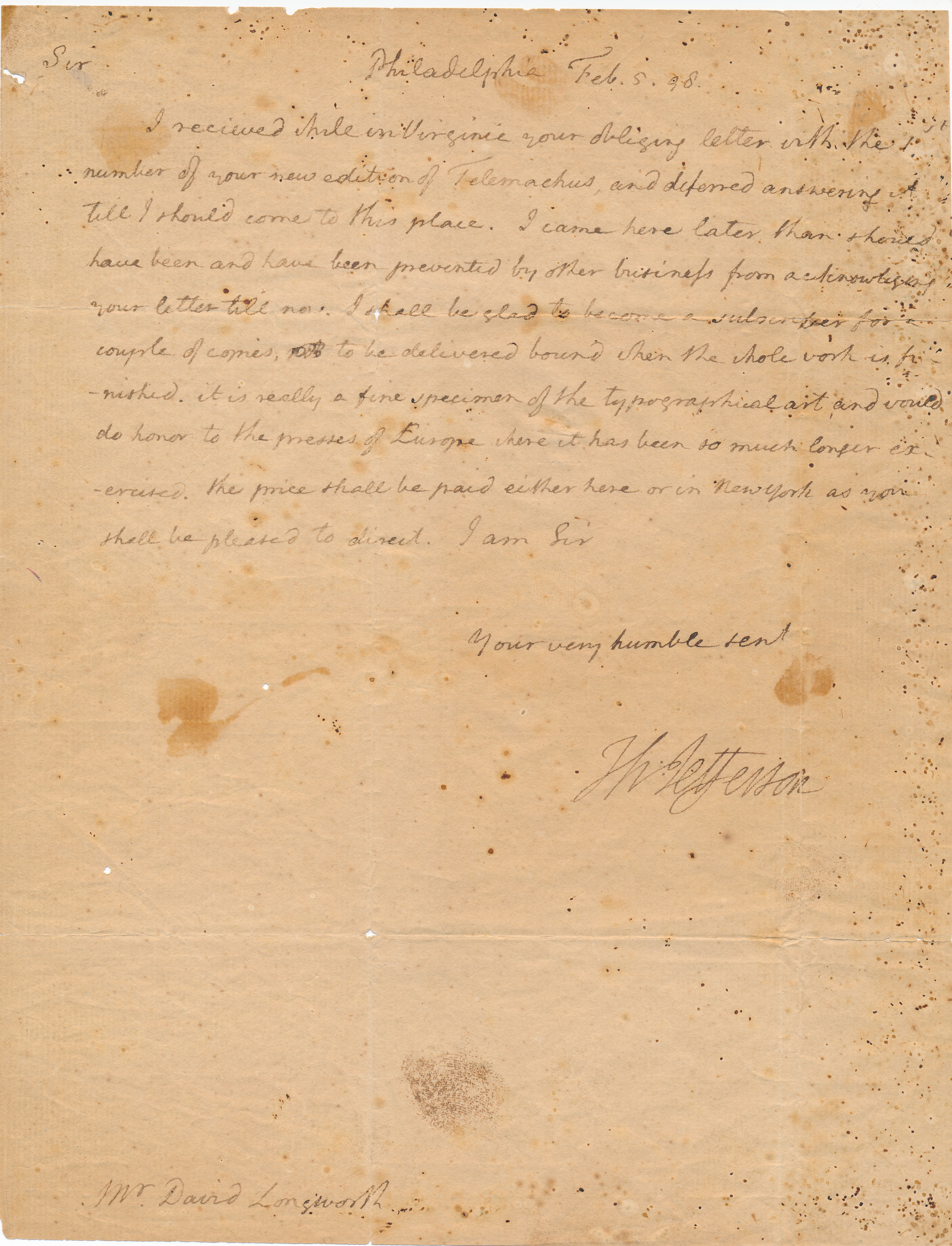

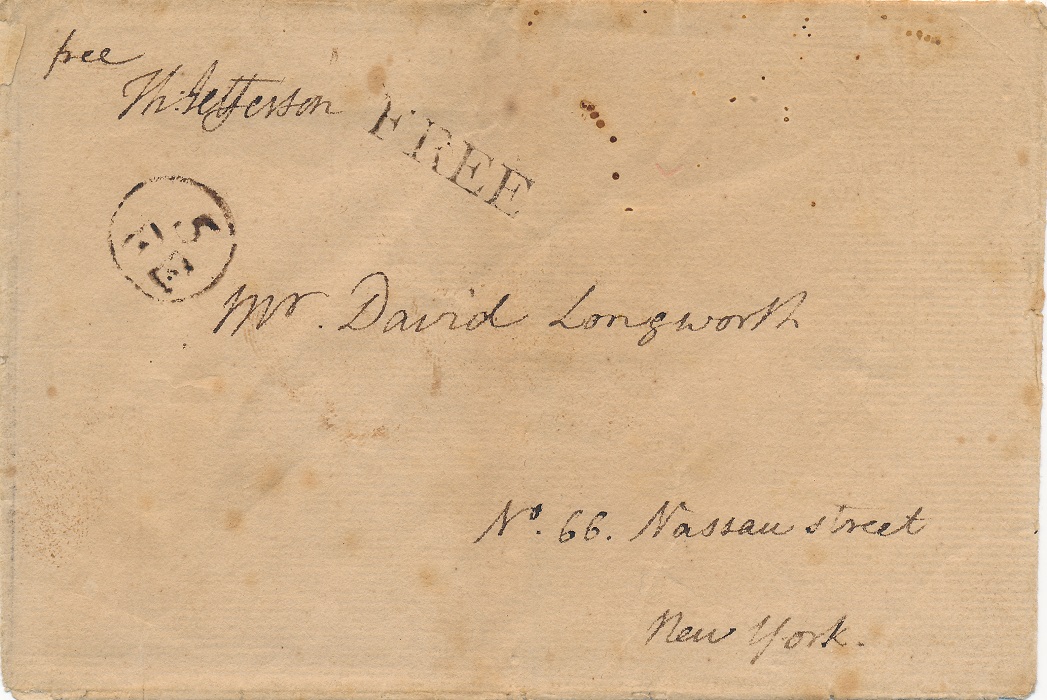

OU's archives and special collections also has a letter written by Vice President Thomas Jefferson in February 1798, which was sent from the nascent nation’s capital in Philadelphia to a friend and New York book supplier named David Longworth.

Longworth, who had recently published a popular New York City directory, printed an English language edition of the political novel The Adventures of Telemachus Son of Ulysses.10 Jefferson requested that he be subscribed to a few copies of the work.

Thomas Jefferson's letter in the special collections of Oakland University Library.

For a transcription of the letter, see Founders Online.

At this time, subscription-based book selling was very popular with both publishers and the reading public. The publisher gained more customers and popularity by publishing the extensive lists of names on their subscription lists, and the subscription business connected publishers and subscribers to distant towns. In order to subscribe to a bookdealer, the recipient would usually write up a contract with the bookdealer. The contract between the two would then list what books the subscriber wanted, the type of paper they would be printed on, the terms of payment and the type used, most of which Jefferson addressed in his letter to Longworth.

It appears that the subscription, although initiated by Jefferson, was directed by Longworth. Jefferson’s stated familiarity with the “presses of Europe” and the “typographical art” in the letter could have referred to his earlier time spent in Europe while producing his own book. “Typographical art,” or the arrangement and style of type used to print, presumably referred to Caslon lettering, the most common type used in the eighteenth century, and the type used for Notes on the State of Virginia.

Recto and verso of the envelope

holding the letter to David Longworth.

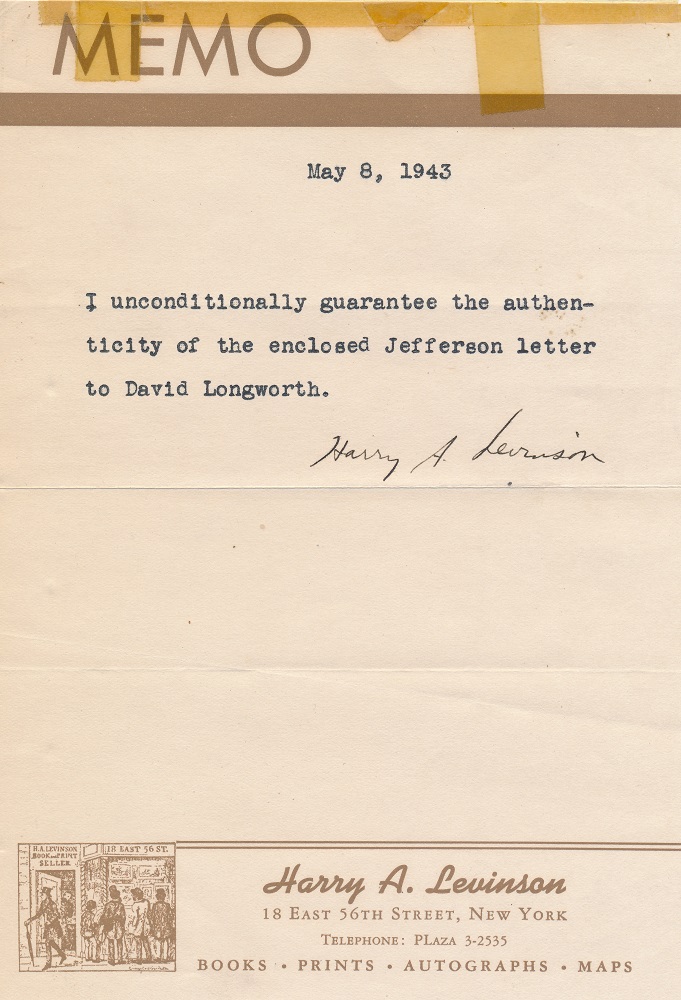

The late New York rare bookdealer Harry A. Levinson authenticated the archive’s Jefferson letter. Levinson was a leading American antiquarian bookseller for over 75 years, and he was a founding member of the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America. Wealthy collectors and other professional bookdealers greatly respected Levinson’s knowledge of the field, and his lifelong career as a rare book dealer attaches an authoritative genuineness to the archive’s letter. Along with the letter and envelope, the archive has a small memo typed out by Levinson in 1943, in which he “unconditionally” attests to the authenticity of the document. Thus, Jefferson’s relationship with New York bookdealers did not end, even after death.11

A Life Full of Erudition

Jefferson never got around to releasing an updated edition of Notes. In the years immediately following the publication of the Stockdale edition, Jefferson made marginal notations and corrections in his own personal copy, which now belongs to the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. He tore out pages with erroneous information and added new content based on sources that he spent a great deal of time verifying. Despite his outward expressions of disinterest, Jefferson still devoted himself in some capacity to the improvement of the book.

Nevertheless, as his public duties to the new American republic grew, this devotion to Notes lessened. Even after Jefferson’s retirement from the presidency in 1809, he found the act of revising and releasing an updated edition impractical, especially considering that he was far more concerned with the administrations of his two fellow Republican successors in the Executive Mansion.12

However, Jefferson’s dedication to reading, writing, and intellectual growth did not stop with Notes. Into his old age, Jefferson continued to write countless letters (some responding to the content of Notes) to family and friends, including his old friend and bitter political rival, John Adams. Thomas Jefferson remains an easily researchable topic for modern scholars today because he documented his life so well in letters, and his intellectual beliefs in Notes on the State of Virginia.

PDF of full text

Ethan Gonzales, Thomas Jefferson: American Bibliophile

Credits

Research and text by Ethan Gonzales during a summer 2019 internship.

Formatted for the web by Dominique Daniel, September 2019

Notes

1. Thomas Jefferson to John Adams, 10 June 1815, Founders Online, National Archives.

2. Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, ed. William Peden (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1955), xi-xv.

3. John B. Boles, Jefferson: Architect of American Liberty (New York: Basic Books, 2017), 167, 171; Jefferson, Notes, xv-xvi.

4. Jefferson, Notes, xvi-xviii; Boles, Jefferson, 171.

5. Jefferson, Notes, xviii; Boles, Jefferson, 171-172; “Notes on the State of Virginia,” Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia, Thomas Jefferson Foundation.

6. Jefferson, Notes, xix-xx; Boles, Jefferson, 172; Thomas Jefferson to John Stockdale, 27 February 1787, Founders Online.

7. John Tebbel, A History of Book Publishing in the United States, vol. 1, The Creation of an Industry, 1630-1865 (New York: R.R. Bowker, 1972), ), 137-138, 140-141, 148-149;. Boles, Jefferson, 172.

8. Tebbel, A History of Book Publishing, 131-133; Jefferson, Notes, xix.

9. The article is pasted on the inside of the front cover, and John Warner’s signature is on the title page, of OU's copy of Jefferson’s Notes, on the State of Virginia […] (Baltimore: W. Pechin, 1800). See also “Gov. John Garland Pollard,” National Governors Association. The author compared John Warner’s signature on the 1800 edition’s title page to John Warner’s autograph on a letter written to Thomas Jefferson. Footnotes from the following letters provided information on John Warner’s public and private careers: To Thomas Jefferson from James Brobson and John Warner, 8 February 1803 and To James Madison from John Warner, 5 June 1812.

10. See footnote for From Thomas Jefferson to David Longworth, 5 February 1798, Founders Online.

11. Tebbel, A History of Book Publishing, 135, 158-159; In 1803, Longworth and Jefferson agreed on the amount of $17.00 for two copies of Telemachus (see Jefferson’s bill [account required]). A brief biography of Levinson lies in the auction catalog for his personal book collection (“Books from the Estate of Harry A Levinson,” Christie’s East, October 9, 1996, 9) and Donald C. Dickinson, Dictionary of American Antiquarian Bookdealers (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998), 124-125.

12. Jefferson, Notes, xx-xxi.

In providing access to its collections, the Oakland University Archives and Special Collections acts in good faith. Despite the safeguards in place, we recognize that mistakes can happen. If you find on our website or in a physical exhibit material that infringes on an individual’s privacy, please contact us in writing to request the removal of the material. Upon receipt of valid complaints, we will temporarily remove the material pending an agreed solution.